The Checklist Manifesto#

Overview#

Atul Gawande, a surgeon, writer, and researcher, wrote The Checklist Manifesto as he explored how to combat the complexities of modern surgery. He argues that checklists can help us reduce errors and establish a higher baseline of performance, not just in surgery, but across almost all professions and disciplines.

How did this come about?#

Gawande was tasked by the World Health Organization (WHO) to help reduce surgical complications and deaths in developing countries. With no resources, he had to find creative solutions that could be implemented across many different countries including different income levels, medical cultures, and levels of medical expertise. Through his research, he found that checklists were a simple yet effective way to improve outcomes in surgery, and, more importantly, in almost any other field.

The Problem#

Humans fail for many reasons. Philosophers Samuel Gorovitz and Alasdair MacIntyre identified three types of human error:1

- Necessary Fallibility: Errors that occur because of the inherent limitations of human cognition and perception.

- Ignorance: Errors that occur because we do not have enough knowledge or information at the time.

- Ineptitude: Errors that occur because we do not apply the proper knowledge or skills, even when we have them.

There is nothing we can do about necessary fallibility, so there is no point in trying to eliminate it. However, the other two types can be improved upon. Before mass communication, electronic records, and the internet, the vast majority of people were simply ignorant of many of the solutions to problems they faced. In today's world, Gawande argues that ignorance is no longer the primary issue. Instead, the volume and complexity of the knowledge required to perform tasks has increased to unmanageable levels, even for experts. Experts have two main difficulties:

- "Fallibility of human memory and attention, especially when it comes to mundane, routine matters that are easily overlooked under the strain of more pressing events."

- "People can lull themselves into skipping steps even when they remember them. In complex processes, after all, certain steps don't always matter...until one day [they do]."

The Solution#

Gawande proposes checklists as part of the solution to these problems. Checklists help ensure that critical steps are not overlooked, even in the most complex situations. They also help establish a baseline of performance, ensuring that everyone follows the same procedures and protocols.

When to use a checklist#

Brenda Zimmerman and Sholom Glouberman differentiate between three types of problems:2

- Simple Problems: Problems that have clear solutions and can be solved with established procedures, such as following a recipe.

- Complicated Problems: Problems that require expertise and analysis to solve, such as sending a rocket to the moon. These problems can often be broken down into smaller, simpler problems.

- Complex Problems: Problems that are unpredictable and require adaptive solutions, such as raising a child or managing an organization. Unlike a rocket launch, every child is different, and there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

For simple problems, a checklist logically fits well, as they can help ensure that established procedures are followed correctly. For complicated problems, a series of checklists can be used, as the problem can be broken down into smaller, more manageable parts. However, for complex problems, procedural checklists may not be directly applicable, as the solutions are often unpredictable and require adaptive thinking. However, Gawande argues that checklists can still be useful in these situations. Instead of providing explicit steps on how to directly solve problems, the checklists can provide a framework for decision-making and ensure that people communicate with each other when necessary. Checklists can be used in almost any situation, just the shape of the checklist will vary depending on the context.

How to write a checklist#

There is a right and wrong way to write a checklist. Daniel Boorman,3 a pilot and a checklist expert for Boeing, explains what makes a good checklist:

- It should not be vague or too long; it should be precise, efficient, and easy to use even in the most difficult situations.

- It should focus on the critical steps that must not be forgotten no matter what.

- It should not be written by outsiders who lack the necessary context; it should be written by the people who will be using it.

- It should not try to spell out everything, educate readers, or treat readers as if they were novices; it should assume a certain level of expertise so that it can be as concise as possible.

With these principles in mind, Gawande outlines a few additional rules for writing effective checklists:

You must define a clear pause point, or trigger moment, when the checklist will be used. This will help ensure that the checklist is used consistently, and only when necessary. After about 1-2 minutes at a given pause point, people will start to lose focus and attention, so the checklist should be designed to be completed within that timeframe.

You must also decide whether the checklist will be a Do-Confirm or a Read-Do checklist. A Do-Confirm checklist is used after the task is completed to confirm that all steps were done correctly. A Read-Do checklist is used during the task to guide the user through each step.

And finally, no matter what, you must test the checklist in real-world situations and revise it based on feedback from users. Every first draft will fall apart when put into practice, so be prepared to iterate and improve the checklist over time.

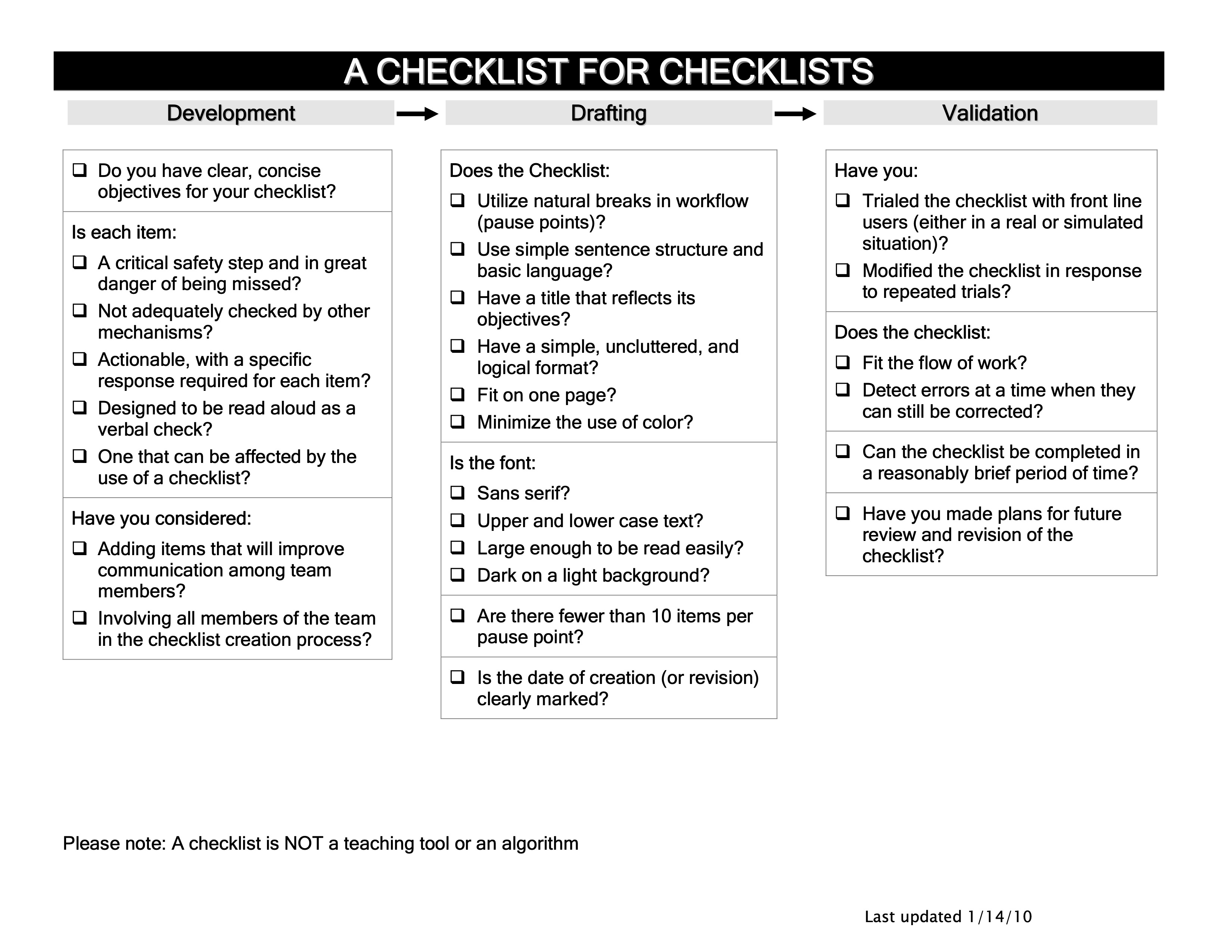

Checklist for checklists#

For your reference, here is a checklist for writing checklists:

It was taken from the appendix of The Checklist Manifesto. You can find other examples of checklists in the book as well.

How to ensure adoption#

Creating a checklist is only half the battle; getting people to use it is the other half. Humans are emotional creatures. They are often resistant to change, and their egos can get in the way of adopting new practices.

To build adoption, Gawande found a few strategies that worked well:

- Force use by putting the checklist in a place where it must be used. For example, in surgery, a checklist was placed on top of the scalpel tray, so that it had to be picked up before the surgery could begin.

- Spread ownership by involving all stakeholders in the checklist, and do not put those in power in charge of operating the checklist. For example, in surgery, when the surgeon was in charge of the checklist, they were more likely to skip steps or ignore it altogether. When nurses were empowered to run through the checklist and confirm that all steps were completed, the checklist was used more consistently. They were able to hold surgeons accountable since they could deflect any pushback to the checklist itself.

- Reflect on the results by tracking outcomes and sharing them with the team. When people see that the checklist is making a difference, they are more likely to use it. For example, Dr. Peter Pronovost tested out checklists in a few different contexts at Johns Hopkins Hospital. He was able to measure patient outcomes before and after the checklists were implemented, and show with statistical significance that the checklists were saving lives. This helped build buy-in from the medical staff.

Once you have some adoption, it should become easier. In the aviation industry, there is heavy buy in to checklists because checklists have been proven to be trusted, and they have been refined over decades of use. It is ingrained in the training and culture. It becomes a self-reinforcing cycle because they truly do improve safety and performance.

Additional Thoughts#

I have been using checklists in my own work and personal life for a few years now. In my personal life, I use TickTick to manage my daily routines like when I wake up and go to bed, my weekly routines like laundry and cleaning, and my monthly routines like budgeting and planning.

In my professional life, I have implemented checklists for all kinds of processes. For example, my team has a checklist for onboarding new team members, which includes all the steps they need to take to get set up with the necessary tools and access. We have checklists for code reviews, deployment processes, and running data pipelines.

The checklists described by Gawande have all been very short, usually just a few items long, and expected to be completed in under two minutes. How To Guides are similar but are a bit more verbose and do a bit of teaching. My team heavily uses How To Guides to help with routine, complex processes. To some extent, these guides are different, but I have found that some of the principles of checklist design still apply.

-

Gorovitz, Samuel, and Alasdair MacIntyre. “Toward a Theory of Medical Fallibility.” The Hastings Center Report 5, no. 6 (December 1975): 13. https://doi.org/10.2307/3560992. ↩

-

Glouberman, Sholom, and Brenda Zimmerman. Complicated and complex systems: what would successful reform of Medicare look like?. Vol. 8. Toronto: Commission on the future of health care in Canada, 2002. ↩